Expanding district heating faster and more sustainably

The world is striving for the so-called "Net Zero Emissions by 2050" as a goal. This means that CO2 emissions are to be completely reduced to zero by...

When the radiators in your flat or house warm up in the morning, it is increasingly likely that this is thanks to a highly integrated supply network: district heating. For local authorities, residential areas, industries, and public institutions, it is now much more than just an alternative to individual boilers – it is key to decarbonisation.

But how does district heating actually work? Why is it so important in the context of municipal heat planning, and how can it be expanded efficiently and in a future-proof way?

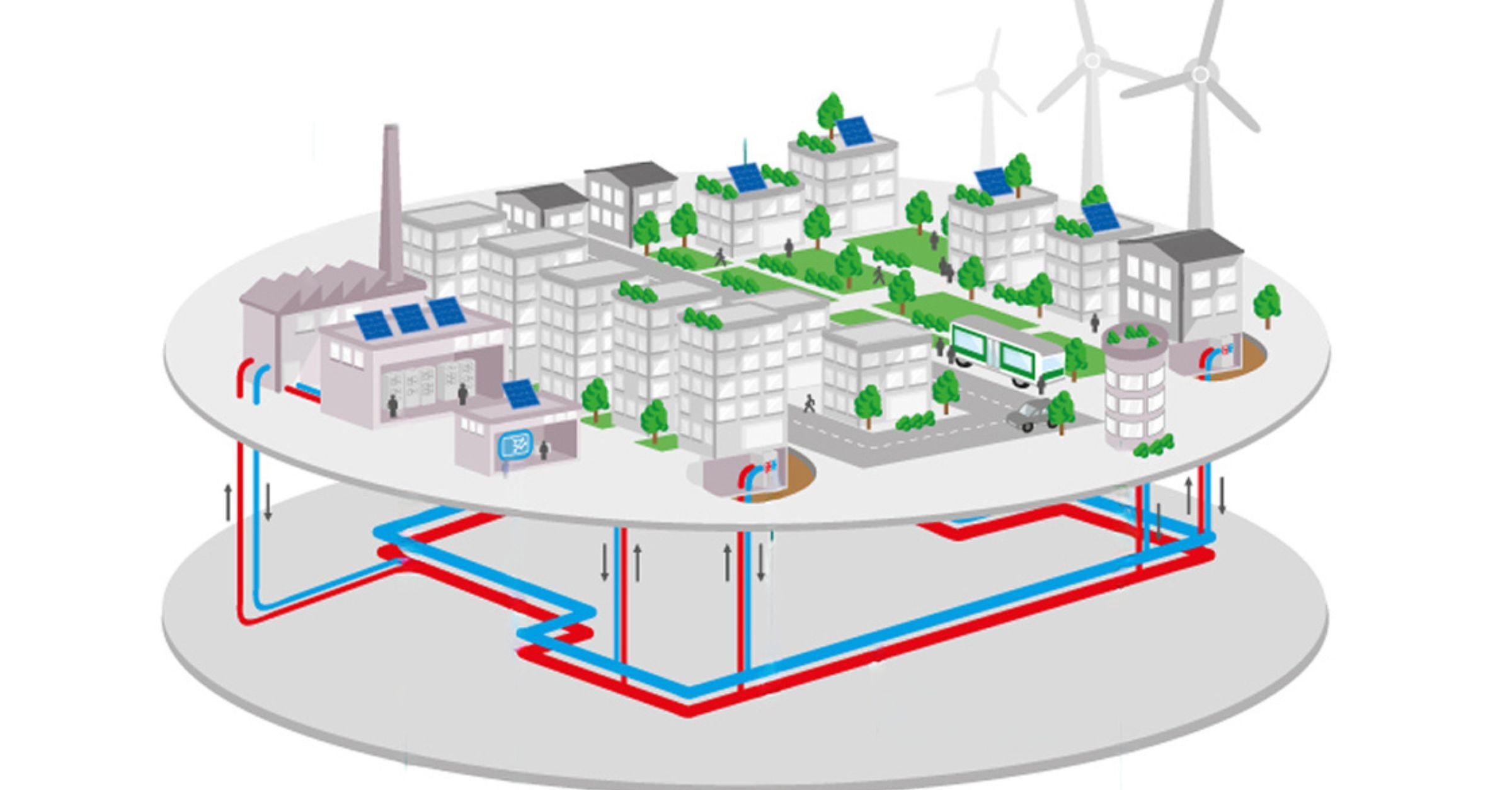

District heating works according to a simple basic principle, and this is precisely where its system strength lies: heat is generated centrally, transported via an insulated pipe network, and used decentrally in buildings. But what exactly is district heating, and what makes it so important?

Four key elements – a closed cycle

District heating starts where energy is concentrated: in combined heat and power plants (usually with cogeneration), large heat pumps, solar thermal systems, or through the use of industrial waste heat. District heating consists of the thermal energy from these sources. The key point is that the source does not have to be located at the point of consumption, as the network efficiently bridges this distance.

A tightly insulated pipe system prevents heat loss and transports the thermal energy – usually as hot water (sometimes steam) – from the producer to the consumers. After the heat has been released, the cooled water flows back in the return pipe to be reheated, creating a closed hydraulic circuit.

In each connected property, a transfer station separates the network circuit from the house circuit. A heat exchanger transfers the energy to the internal heating system.

Pumps, storage tanks, sensors, and control technology ensure that the pressure remains stable, the temperature is adjusted to demand, and the system responds flexibly to varying consumption patterns.

Why the return flow determines efficiency

A key objective of the district heating concept is to minimise the return temperature. The greater the temperature difference between the flow and return, the more energy can be transferred per litre of water. In research on 4th Generation District Heating (4GDH), the return temperature is considered a key factor in system efficiency. According to studies by Aalborg University and the International Energy Agency (IEA), consistently lowering the return temperature can reduce network losses by up to 30% while also making new heat sources such as industrial waste heat below 60°C usable.

For district heating to reach its destination efficiently and with minimal losses, a precisely coordinated combination of route planning, material selection, control technology, and hydraulics is required. A modern district heating network is divided into four central components:

These transport district heating from the production site to the main consumption points. Depending on the transport capacity, the diameter can be up to 1.2 metres.

District heating is fed into streets and neighbourhoods via smaller pipe cross-sections. The network branches out similarly to electricity or drinking water network – but with specific hydraulic features.

Each connected building has its own pipe entry, always as a double-pipe system (flow/return).

To ensure that heat is reliably delivered to every connected building, the flow of hot water is constantly monitored and adjusted. Pumps, valves, and sensors ensure sufficient pressure and the correct water flow – regardless of how many buildings currently require heat or how much outside temperatures fluctuate.

Flow, return – and what matters in between

Hot water (depending on the network generation) flows through the pipe system at temperatures between 70 and 130 °C. After the heat is released in the building, it returns through the return pipe at approx. 40 to 70 °C. The hydraulic balance between supply, consumption, and return flow is crucial for comfort, network stability, energy efficiency, and pressure maintenance.

Materials and installation: why technology under the street is crucial

Pipe systems form the physical backbone of a district heating network. They must withstand high temperatures, pressures, and corrosion risks for decades.

Typical material used:

Underground installation is standard: the factory-insulated pipe is laid directly in the ground.

Insulation: the first line of defence against energy loss

Every pipe loses heat – the crucial factor is how much. High-quality insulation materials, such as rigid polyurethane foam with a low λ value (< 0.024 W/mK), significantly limit these losses. In conjunction with a diffusion-tight outer shell and controlled installation, heat loss can be kept below 5%, even over long distances.

The transfer station is the invisible hub between the public network and a building’s internal heating system. What may appear as an inconspicuous box in the basement is, in face, a finely tuned system that plays a key role in comfort, efficiency, and network stability.

What happens in the transfer station?

The central task of a district heating station is to transfer the energy carried in the network safely, controllably, and efficiently to a building’s internal heating system – without direct water contact between the primary and secondary circuits.

Core components at a glance:

Material resistance requirements

Transfer stations operate under demanding conditions: changing temperatures, fluctuating pressures, and varying water qualities depending on the region. All materials used – especially seals, plate packs, sensors, and valve housings – must be designed to withstand these stresses.

Typical stress scenarios:

Plastic-based systems offer advantages in the secondary circuit (building side) when working with low flow temperatures (e.g. < 80 °C).

Pipe systems are not passive infrastructure. They are technical performance carriers that transport district heating and determine how efficiently, sustainably, and economically a network operates – as we as whether it is ready for the challenges of tomorrow: lower temperatures, decentralised feed-in, and more flexible operation.

Anyone planning district heating systems or renovating network sections today therefore needs to consider more than just materials and prices. Functional parameters are crucial: pressure and temperature resistance, chemical resistance, installation flexibility, sealing reliability, and, last but not least, service life under real-world conditions.

District heating has long been a closed, centralised system: high temperatures, large heating plants, and unidirectional distribution. But this picture is currently undergoing a fundamental change – technologically, structurally, and regulatorily. The next generation of district heating networks will no longer be purely centralised; they will be more decentralised, cooler, and smarter. These networks will also transform the system into a platform for a wide variety of heat sources.

4GDH: Fourth-generation district heating

Fourth-generation district heating (4GDH) is not a product, but a paradigm shift: moving away from fossil fuel-dominated high-temperature networks towards lower-temperature, open-source, and bidirectionally controllable systems.

Key features:

5GDHC: District heating becomes bidirectional

The fifth generation of district heating and cooling systems (5GDHC) goes one step further. It almost completely dispenses with central high-temperature sources. Instead, the network operates at very low temperatures (usually between 10°C and 40°C), at which reversible heat pumps in the buildings generate the final useful temperature.

Pilot projects such as ‘Ectogrid’ in Sweden demonstrate that 5GDHC systems work particularly efficiently in mixed-use neighbourhoods (residential, commercial, data centres), as heat demand and waste heat sources – for example, waste heat from the data centres – locally balance each other out.

Regulatory tailwind: EU & BEW

The political direction is clear. The EU Commission defines the decarbonisation of the heating and cooling sector as indispensable for achieving climate targets. In its ‘Heating and Cooling’ strategy, it emphasises that 50% of the EU's final energy consumption goes into these sectors – the majority of which is still fossil-based.

According to Euroheat & Power, up to 50% of Europe's heat supply could be provided by district and local heating networks by 2050, provided that 4GDH and 5GDHC are scaled up.

Efficiency begins under the street. District heating only reaches its full potential when the infrastructure grows with it – not only in terms of quantity, but also in terms of quality. Behind every successful network there is one clear parameter: the right pipe systems. Pipes that remain leak-proof for decades, retain their insulating properties, and adapt flexibly to urban structures enable network expansion without the need for subsequent renovation loops.

aquatherm supports you in the selection, design, and implementation of high-quality piping systems, tailored to your temperature regime and installation conditions.

Contact us now and start your project check.

The world is striving for the so-called "Net Zero Emissions by 2050" as a goal. This means that CO2 emissions are to be completely reduced to zero by...

Data centres are growing in size and performance, and with them the demands on efficient refrigeration cycles. According to the International Energy...

At first glance, the question of how district heating is produced and what it consists of may seem simple, but it touches on central aspects of the...